|

|

|

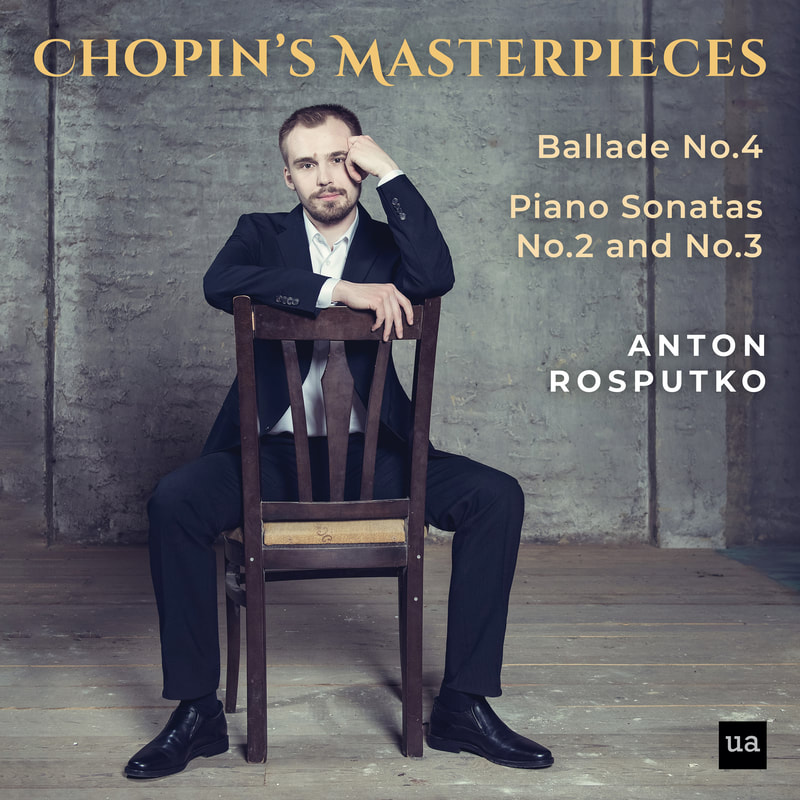

Anton describes his thoughts behind the album:

‘If somebody asked me about the main challenge during recording and playing Chopin’s 4th Ballade and the 2nd and 3rd Piano Sonatas, my answer without hesitation would be: to offer something new in this music, so long been an inseparable part of the culture of classical music lovers for generations, while staying sincere and far from artificial decisions foreign to my genuine view of the works.

These pieces are a seduction for a pianist, a desirable professional and artistic challenge that cannot be resisted, even if there are already hundreds if not thousands recordings of the same music. We all know that there are dozens of piano compositions that have received so many performances that often we want to restrain ourselves from listening to them. The 2nd and the 3rd Chopin’s Piano Sonatas appear frequently in recitals (the 2nd especially, not to mention outside-of-concert performances of the 3rd movement, the Funeral March), and the 4th Ballade is the most played of the Ballades. However for me the beauty and possibilities of these works are never exhausted, whether listening or playing them. I have been contemplating the reason: a possible answer lies in Chopin’s raw emotions – as raw and true as can be, and the absence of “concert stage effects” – emotions which already evoke so much trust in a listener. This is especially relevant for the 4th Ballade. The introversion of this music remains shocking despite its open outbursts of emotion that culminate in the desperate coda.

Chopin composed several works that were meant to provide a charming and brilliant cherry on the top of his concert programmes, with virtuosity proclaimed openly by the use of term ‘Brilliante’ in their titles. In the works recorded here however, virtuosity is truly nothing but the server of a function – a speed necessary for a certain expression, as in the apocalyptic kaleidoscope of the 4th Ballade’s coda, or the whirling runs in 2nd Sonata’s ‘Presto’. The 3rd Sonata’s Finale is close to Chopin’s concert rondos, but far from their intent to please the audience merely with entertainment, and equally far from declaring self-satisfaction, even in its joyfully glowing B Major conclusion.

These works are true masterpieces, on which I have tried to work with sustained artistic attention and respect towards the music itself, and I am delighted to present my personal rendition of them to you.’

Anton Rosputko

About Anton Rosputko

Anton Rosputko was born in Jūrmala, Latvia, in 1993. Interntional awards include 1st Prize, Gradus ad Parnassum Competition, Kaunas, Lithuania; Third Open Russian Competition in Kaliningrad, 2nd Prize, Virtuosi per musica di pianoforte, Ústí nad Labem (Czech Republic), 3rd Prize; Schumer Prize in Enschede (Netherlands), 2nd Prize (2007) and 1st Prize (2010) at the Jūrmala International Competition. His main mentors have been Tatyana Pavlyuchenko, Jānis Maļeckis, Pavel Gililov and Boris Petrushansky.

Anton Rosputko received a Latvian Ministry of Culture prize in 2005, 2006 and 2008, as well as a Latvian 'Recognition Award' in 2009. In 2012 he received the Hübel Foundation Scholarship. He is a prize-winner of the Mozarteum International Summer Academy (Salzburg, Austria, 2009), including performing in the Salzburg Festival.

Anton has also taken part in masterclasses with Armen Babakhanian, Arkadiy Sevidov, Pavel Gililov, Sergej Maltsev, Anatol Ugorski, Peter Tacács, Jacques Rouvier, Matti Raekallio, Siegfried Mauser, Wolfgang Manz, Boris Petrushansky and Denis Proshayev.

Anton Rosputko was a participant of the Kaunas Festival in Lithuania in 2006 and 2010. As a soloist with orchestra he has performed with the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra and Normunds Vaicis, Sinfonia Concertante Orchestra with Andris Vecumnieks, Kaunas City Orchestra and Modestas Pitrenas, Liepāja Symphony, and Amber Sound Orchestra with Tadeusz Wojciechowski. Anton Rosputko has performed widely in Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, Italy, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and the Netherlands. Venues include the Great Hall and the Vienna Hall of the Mozarteum Foundation, Solitär Hall of the Mozarteum University, Great Concert Hall of the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich, Great Hall of the University of Music and Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Theatre Leipzig, Concert Hall of Kaliningrad Philharmoniс Society, Great Hall of Kaunas State Philharmonic Society; the Small Guild, Riga House of Moscow, Great Hall of Latvian National Opera and Dzintari Concert Hall.

www.antonrosputko.com

„Wenn mich jemand über die Hauptherausforderung beim Aufnehmen und Spielen von Chopins 4.Ballade und der 2. und 3.Sonate fragen würde, wäre meine unverzügliche Antwort so: etwas neues in dieser Musik anbieten, die so lange ein fester Teil der Kultur von mehreren Generationen der Liebhaber von der klassischen Musik gewesen ist, und dabei ehrlich und weit von künstlichen Entscheidungen bleiben, die meiner natürlichen Beziehung zu diesen Werken fremd sind.

Diese Werke sind eine Verführung für Pianisten, eine gewünschte professionelle und künstlerische Herausforderung, der man nicht widerstehen kann, auch wenn es schon Hunderte, wenn nicht Tausende Aufnahmen derselben Musik gibt. Wir wissen alle, dass es Dutzende von Klavierkompositionen gibt, die so viele Aufführungen erlebt haben, dass wir oft uns davon distanzieren wollen, sie zu hören. Die 2. und die 3. Sonaten Chopins erscheinen in Solokonzerten häufig (besonders die 2., ganz zu schweigen von nicht-Konzertaufführungen des 3.Satzes, „Marche funèbre”), und die 4.Ballade ist von allen die am meisten gespielte. Jedoch sind für mich die Schönheit und das Potenzial dieser Werke nie erschöpft, egal, ob ich sie höre oder spiele. Ich habe über Ursachen nachgedacht: eine mögliche Antwort liegt in Chopins rohen Emotionen – so roh und wahrhaft wie es sein kann, ohne „Konzertbühneneffekte“ – Emotionen, die so viel Vertrauen beim Zuhörer hervorrufen. Das ist besonders für die 4.Ballade relevant. Diese Musik ist unglaublich introvertiert, auch wenn sie ab und zu emotionelle Aufschwünge bekommt, die in der verzweifelten Coda ihren Höhepunkt haben.

Chopin komponierte einige Werke, die dafür gedacht waren, ein charmantes und brillantes Sahnehäubschen für seine Konzertprogramme zu schaffen, mit der Virtuosität, die öffentlich mit dem Begriff „Brilliante“ in ihren Titeln angekündigt wurde. Jedoch macht in den hier aufgenommenen Werken Virtuosität wirklich nichts anderes als eine Funktion – die für bestimmten Ausdruck notwendige Geschwindigkeit, wie im apokalyptischen Kaleidoskop der Coda in der 4.Ballade, oder in den wirbelnden Läufen im „Presto“ der 2.Sonate. Das Finale der 3.Sonate ist Сhopins Konzertrondos nahe, aber weit von ihrem Ziel,, das Publikum lediglich mit Unterhaltung zu befriedigen, und genauso weit davon, Selbstbewusstsein zu erklären, sogar in seinem froh glänzenden Schlussteil im H-Dur.

Diese Stücke sind echte Meisterwerke, während der Arbeit an welchen ich versuchte, mit ständiger künstlerischen Aufmerksamkeit und Respekt gegenüber der Musik selbst zu bleiben, und ich freue mich, meine persönliche Interpretation von ihnen für Sie zu präsentieren.”

|

|

|